Regarding the following matters, my fellow believers, rejoice in the Lord. I do not hesitate to write these same things to you, because they contribute to your security.

(Philippians 3:1 TBA)

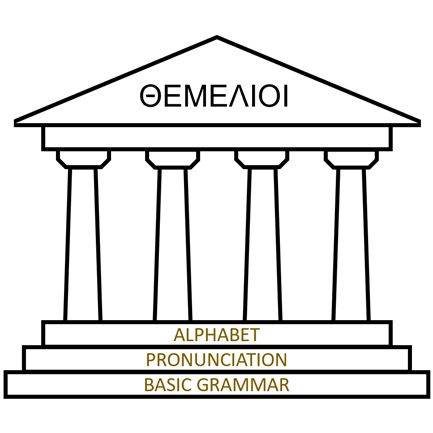

Introduction

In my previous post I began commenting on the New Testament book of Acts. In this post I will continue my comments.

The Four Gospels are followed by the book of Acts, a history of the early Christian church, that continues the story where the Gospels leave off. Specifically, Acts is a sequel to the Gospel of Luke written by the same author (Luke) to the same person (Theophilus), probably not long after the Gospel of Luke was written.

Acts describes the EXPANSION of the Good News to the whole world as Christians obeyed Jesus’ command to be witnesses to the ends of the earth.

In my previous post I commented on chapters 1 through 12. The focus of Acts up to that point had been the expansion of the Good News to Jerusalem, Judea, and Samaria. But beginning in chapter 13, the book shifts its focus to Paul and his three extensive missionary journeys “to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

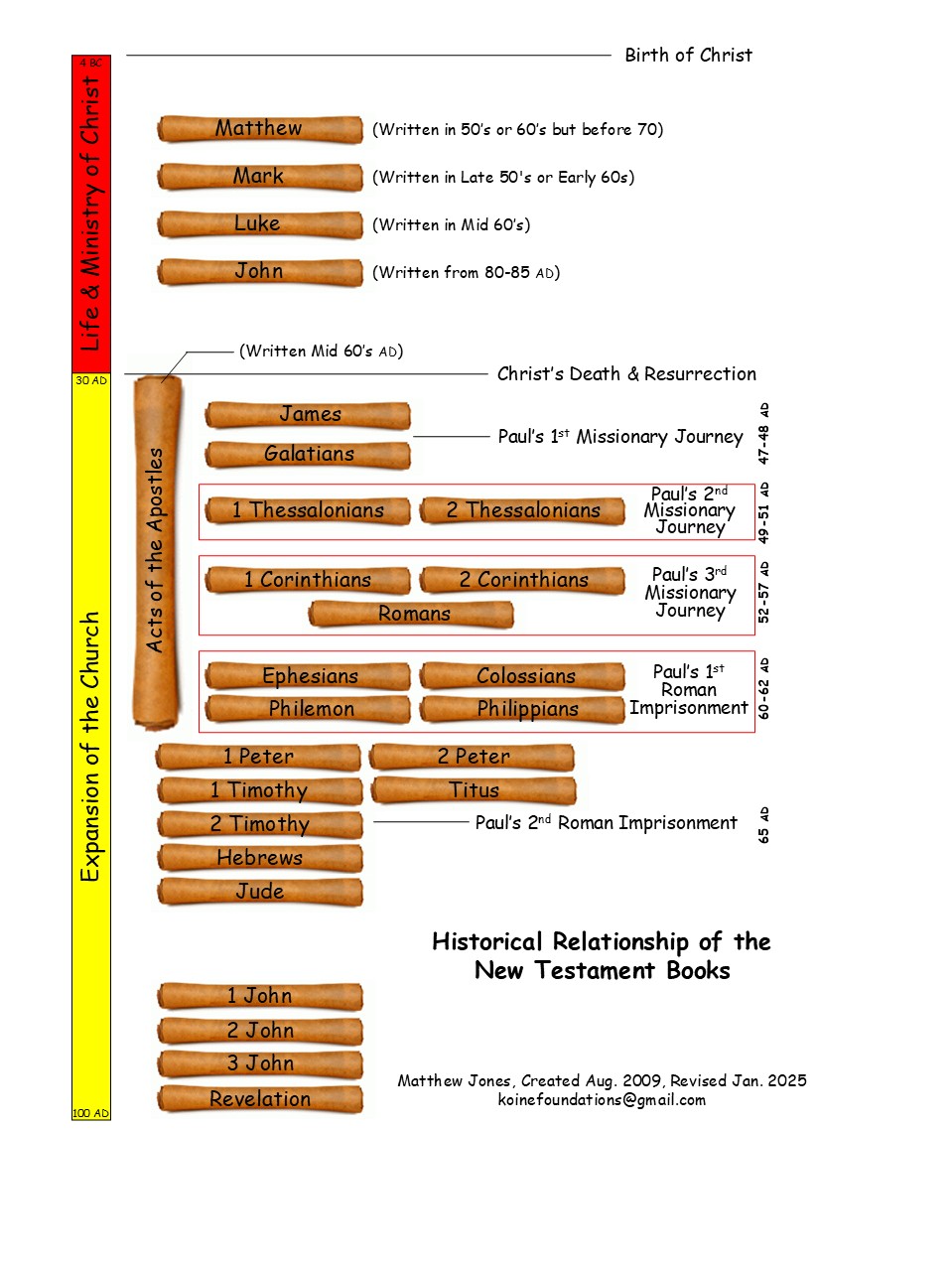

A number of other New Testament books that were written by Paul fit into the events recorded in Acts chapters 13 to 28. So, I will continue my comments starting at chapter 13 by pointing out the major events and showing where these other New Testament books fit in.

Epistles

The Good News rapidly spread throughout the Roman world as believers preached the Good News. But as the message spread, so too did confusion about how to live in light of the message of the Good News, especially for people who came from pagan backgrounds. 1

The Epistles (i.e., Letters) that follow the book of Acts in the New Testament are letters written by the first generation of Christian leaders such as Paul, John, and Peter, to church communities or to individuals to explain how to live in light of the Good News. 2 Eleven of them were written during the events described in the book of Acts (James to Philippians as shown on the chart above). The rest were written after the events in the book of Acts (1 Peter to Revelation on the chart above). This chart shows the order in which they were written, not their order in the New Testament. (Regarding their order in the New Testament, see my post: What is the New Testament Canon?)

The Epistles were written to instruct Christians how to behave as they serve Christ in this world and wait for the return of Christ. 3 Their culture was not much different than ours today – pagan, permissive, sex-oriented, governed by situational ethics. So, what is written in these New Testament books is relevant for us today. They explain the APPLICATION of the Good News to daily living in a corrupt culture.

The word ‘epistle’, simply means ‘letter’. The English word ‘epistle’ is a transliteration of the Greek word ἐπιστολή / epistolē which is the term for written communication in the form of a letter. So, the twenty-two New Testament books called Epistles were communicated to us through personal letters written to church communities or individuals. They make up about 35% of the content of the New Testament.

Early Christianity grew rapidly and broadly because of its missionary zeal, so a personal letter was the best means for communication, often to address an urgent issue. The letters include a mixture of doctrine and practical instructions.

It was a common practice during New Testament times for an author to dictate to a writing secretary, called an amanuensis. Sometimes the author gave this amanuensis a degree of freedom in the structure of the letter and choice of words.

An example of this use of a amanuensis is seen in Romans 16:22, where Tertius identifies himself as the one who wrote down the letter.

I Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord. (Romans 16:22 ESV)

Apparently, Paul dictated to Tertius what he wanted to say in the letter.

The Epistle of James

Author: James, a brother of Jesus

Audience: Jewish believers spread throughout the Roman empire

Date: Early to mid 40’s AD

In the previous post, I ended with Acts chapter 12 and the wave of persecution that began with the execution of James, the brother of the Apostle John.

About that time Herod the king laid violent hands on some who belonged to the church. He killed James the brother of John with the sword, and when he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also. (Acts 12:1-3 ESV)

Shortly after the execution of James, the first book of the New Testament was written – the Epistle of James. It was written by a different James – James the brother of Jesus. James was a common name in New Testament times and there are three prominent men with this name mentioned in the New Testament:

- James, the brother of John who was executed by Herod in 44 AD.

- James, the brother of Jesus who wrote the Epistle of James.

- James the Less (Younger), one of the Twelve Disciples.

James, the brother of Jesus, was not a believer during the earthly life of Jesus (John 7:2-8), but was a witness of the resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:7), and was present on the day of Pentecost (Acts 1:14). He became a leader of the early church in Jerusalem. He was a strict Jew and strictly adhered to the Jewish law (Galatians 2:12).

For the first 15 years after Jesus’ resurrection, the home of the church was based in Jerusalem, and most believers were Jewish. In this early environment of a primarily Jewish-Christianity, James wrote his letter to Jewish Christians scattered around the world.

The book of James gives practical instructions for living the Christian life, dealing with issues like pride, discrimination, greed, and backbiting.

As I mentioned in previous posts, there is a way of life implied by accepting the Good News. The Epistle of James makes the point that genuine Christian faith becomes evident in works of love and obedience. The fact that a person is a believer will be evident and demonstrated in what they think, say, and do (James 2:17).

So, James admonishes believers:

But be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves. (James 1:22 ESV)

James also warns that trials and suffering will be part of accepting the Good News. Believers will be persecuted for demonstrating their faith through what we think, say, and do.

Paul’s First Missionary Journey

Reference: Acts Chapters 13-14

Date: 47-48 AD

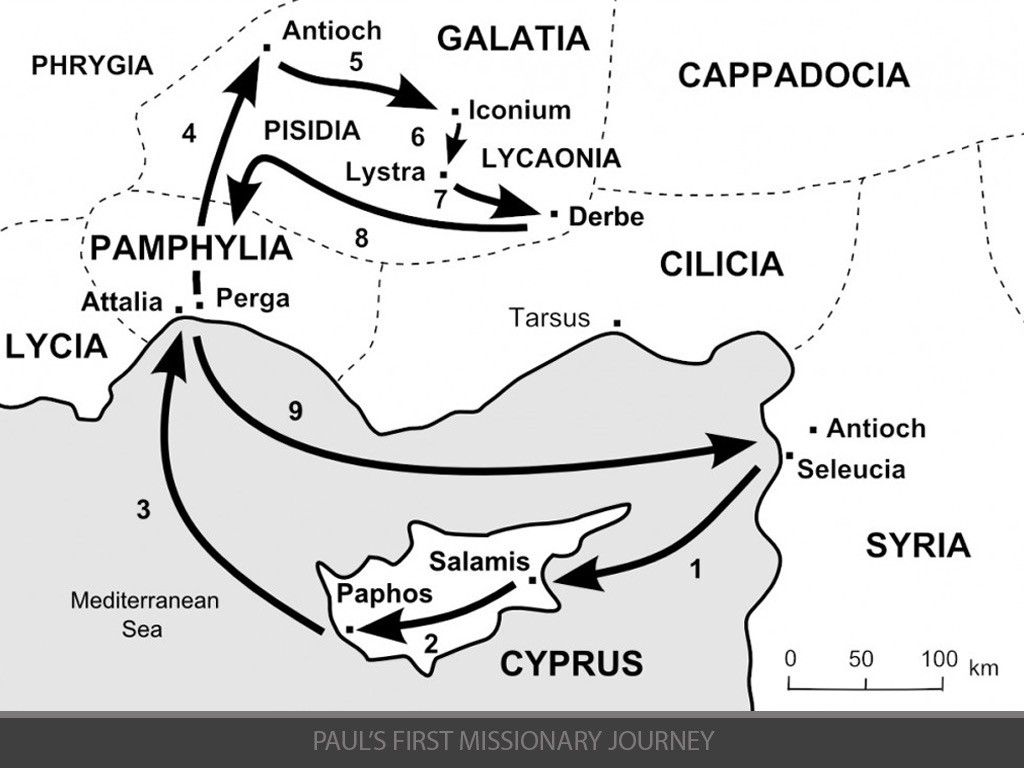

Around the time James wrote his epistle, Paul, Barnabas, and Mark (who later wrote the Gospel of Mark) were sent out by the Church in Antioch on what would be Paul’s first missionary journey.

They evangelized on the island of Cyprus (the home of Barnabas) and in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). Their practice was to first preach in the Jewish Synagogues. When opposition arose from the Jews, they would then preach to the Gentiles.

They had a lot of success evangelizing in the province of Galatia. In the city of Lystra (#7 on map), they were mistaken as the gods Jupiter and Mercury when Paul healed a lame man. But the Jews eventually turned the crowds against them, and Paul was stoned and dragged out of the city, assumed to be dead. But he revived and went back into the city to continue preaching the Good News.

After Paul and Barnabas left, apparently some Jewish believers came into the areas they had evangelized and began teaching the new Gentile believers that to be ‘real’ Christians they must follow the Old Testament law, including being circumcised. Those who taught this were called Judaizers.

The Jerusalem Council

Reference: Acts Chapter 15

Date: 48 or 49 AD

At the end of their missionary journey, Paul and Barnabas returned to Antioch. While there, some Judaizers arrived from Judea who told the Gentile believers in Antioch that unless they were circumcised and followed other Jewish laws, they could not be saved. Paul and Barnabas strongly disagreed with them. To resolve the issue, the church in Antioch sent Paul and Barnabas to Jerusalem to discuss the issue with the apostles and elders.

The conversion of large numbers of Gentiles forced the Church to face an important question. Many of the first Christians were Jewish and continued their Jewish manner of life – attended synagogue, offered sacrifices, observed the dietary restrictions of the Old Testament. So, the question naturally arose, “Should Gentile Christians also be required to submit to circumcision and practice the Jewish way of life?”

This became such an important issue, that a Church council was held in Jerusalem to resolve the matter permanently (48 or 49 AD). This event is recorded in Acts 15.

James, the brother of Jesus and the leader of the Church who we met earlier, who was a strict follower of the Old Testament law, issued a letter of the council’s decision. It is recorded in Acts 15:22ff. It declared that Gentile believers did not have to follow the Old Testament Law to be saved. This opened a new era for the expansion of the Good News to the world.

The Epistle to the Galatians

Author: Paul

Audience: Gentile believers in the province of Galatia (see map above)

Date: 48 or 49 AD

Either before or after this council, Paul wrote his first letter, the Epistle to the Galatians. It was addressed to believers in the area of Paul’s first missionary journey, where Gentile believers were being bothered by Judaizers (see Galatians 1:6-7). In his epistle, Paul argues that salvation is not by any human effort or works, like obeying the Law. It is by grace alone through faith in Jesus Christ and not Jesus Christ plus anything else.

We know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ. (Galatians 2:16 ESV)

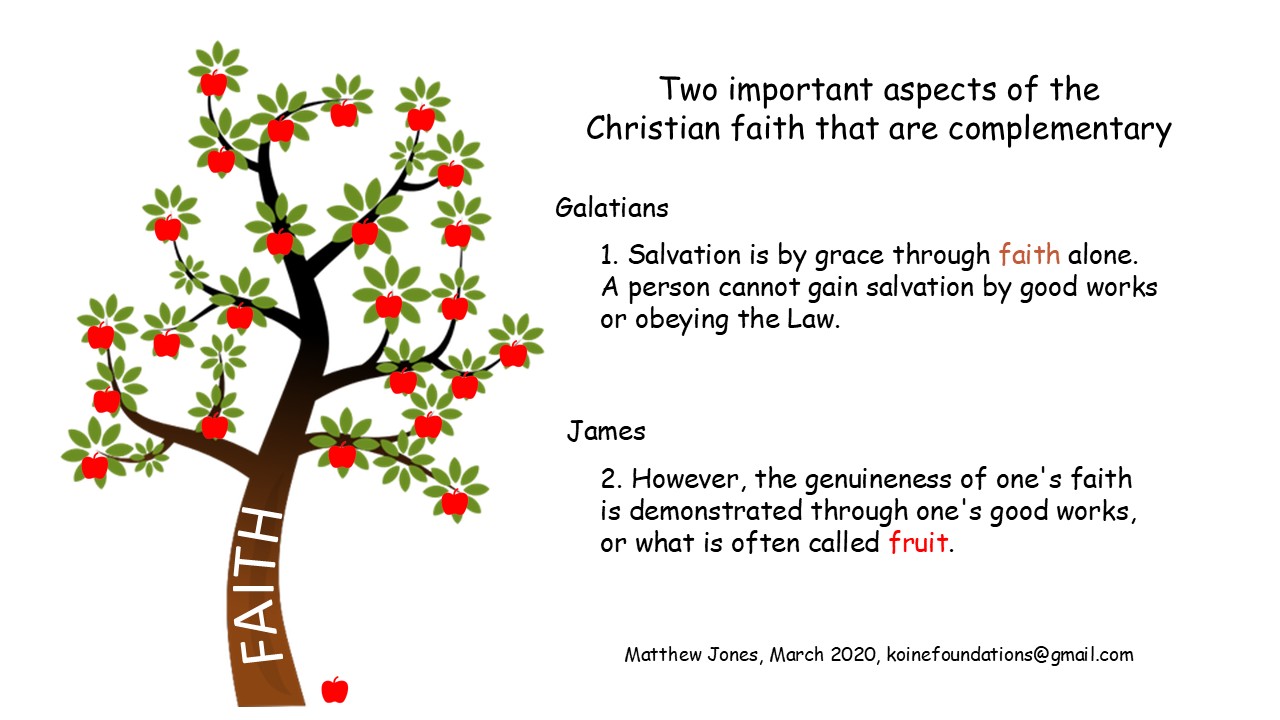

The first two books of the New Testament that were written, James and Galatians, show two important complementary aspects of the Christian faith:

(1) Galatians: Salvation is by grace through faith alone. A person cannot gain salvation by good works or obeying the Law.

(2) James: However, the genuineness of one’s faith is demonstrated through one’s good works, or what is often called ‘fruit’. (See also Matthew 7:20.)

Howard Vos gives the following useful illustration of these two truths:

To steer a straight course in a rowboat, one must have two good oars and apply equal strength to each. The oars necessary for steering a straight course in the Christian life are found in Galatians and James. The former stresses justification by faith and the latter, works as an evidence of faith. These truths are supplementary, not contradictory; and the neglect of either may ground one on the sandbars of spiritual catastrophe. 4

In the next post I will continue with my comments on the book of Acts.

Word Focus Lexicon

Lexical Form: ἐπιστολή -ῆς, ἡ

Transliteration: epistolē

Gloss: letter

Part of Speech: Feminine Noun

New Testament Frequency: 24

Strong’s Number: G1992 (Link to Blue Letter Bible Lexicon)

The word ἐπιστολή / epistolē is typically used in the New Testament to refer to written communication in the form of a letter. 22 of the 27 books of the New testament are actually epistles or letters. They were written by various Christian leaders to individuals or church communities. They teach important doctrines, address local problems in the churches, and provide instructions for believers to live holy and Christlike lives.

Footnotes

[1] Dickson, John. A Doubter’s Guide to the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014 by John Dickson.) Page 189.

[2] Ibid., page189.

[3] Ibid., page199.

[4] Vos, Howard F. Beginnings in the New Testament. (Chicago: Moody Press, 1973 by The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.) Page 94.

Bibliography

Balz, Horst and Schneider, Gerhard, Editors. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1990.

Beetham, Christopher A., Editor. The Concise New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis. Zondervan Academic, 2021.

Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Abridged in One Volume. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1985.

Bruce, F.F. Commentary on the Book of the Acts, The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Reprinted 1984.

Carson, D. A. and Moo, Douglas J. An Introduction to the New Testament. Zondervan, 1992, 2005 by D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo.

Danker, Frederick William. The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament. The University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Dickson, John. A Doubter’s Guide to the Bible. Zondervan, 2014 by John Dickson.

Gilbrant, Thoralf, International Editor. The New Testament Greek-English Dictionary. The Complete Biblical Library, 1990.

Gundry, Robert H. A Survey of the New Testament. Zondervan Publishing House, 1970.

Guthrie, Donald. New Testament Introduction. Inter-Varsity Press, 1970 by The Tyndale Press.

Liddell, Henry George and Scott, Robert. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford University Press. 1940. With a Supplement, 1996.

Marshall, I. Howard. The Acts of the Apostles, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1980 by I. Howard Marshall.

Tenney, Merrill C. New Testament Survey. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1953, 1961, 1985.

Verbrugge, Verlyn D. New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology: Abridged Edition. Zondervan, 2000.

Vos, Howard F. Beginnings in the New Testament. Moody Press, 1973 by The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago

English translations of Bible verses marked (TBA) are translations by the author from the Greek text and are not quotations from any copyrighted Bible version or translation.

Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are from the Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © 2001, 2007, 2011, 2016, 2025 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment